True Words, Inadequate Instruments: Pontificating About God Without Pretending to Comprehend Him

“If you have understood, then what you have understood is not God.” (often attributed to St Augustine)

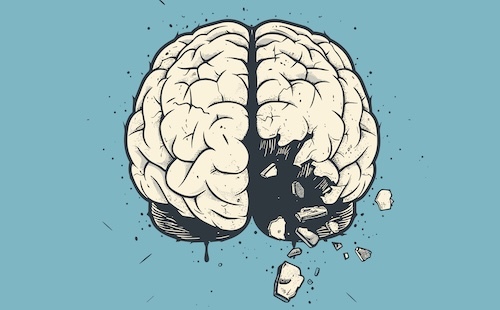

Every theological work, formulation, even dogma, is a true confession in human words of realities that ultimately exceed us. There is no way human language or understanding can exhaustively explain or describe God’s unknowable essence. We only know as creatures can know, “as through a glass, darkly” (1 Cor 13:12). In that sense, all our God-talk is symbolic and analogical, not because it’s false, but because created speech simply can’t contain the Uncreated (Aquinas, ST I, q.13).

So even revealed, infallible truth is still grasped dimly on our side, not because truth is subjective, but because we are finite. There is no univocal, “God-sized literal” available to us. We can say what is truly the case, but we can’t say it in a way that drains the mystery. It’s like that old thought experiment: what’s it like to be a bat? You can speak truly about bats, define their biology, map their behavior, but you can’t enter bat-consciousness by way of definitions.

In that sense, the Mohammedans are onto something when they emphasize God’s incomprehensibility, but they push it too far, collapsing God into sheer distance. The Holy Spirit, through the Church, really does guide us into all truth, giving us genuine knowledge of God, especially through His self-revelation and His acts. Just not in the way we comprehend a math problem. I can’t comprehend what it’s like to be outside space and time, or what it’s like to be a soul separated from its dead body, much less what it’s like to be a pure intellect, or what it’s like to be raised and glorified, partaking of the infinite divine nature (2 Pet 1:4). I’m a man with limited knowledge. Even the best magisterial or conciliar pronouncements are still careful, guarded speech about a hierarchy of realities that remain bigger than my mind, and bigger than my words (Dionysius, Divine Names).

This is why so much of the “last things” in Sacred Scripture comes to us in symbolic and apocalyptic imagery. Not cartoon props, but true signs pointing beyond themselves: the lake of fire, outer darkness, the worm that does not die, gnashing of teeth, Gehenna, unquenchable fire, smoke of torment, the second death, the books opened, the throne and the judgment.

And on the other side, the wedding feast, the Bride, the new heavens and new earth, the New Jerusalem, the river of the water of life, the tree of life, crowns, robes, harps, gold and precious stones, gates of pearl, even the sea being no more. These aren’t “mere metaphors” in the thin sense, and they aren’t a set of literal camera angles either. They’re symbolic because they’re trying to speak truly about realities that overflow our categories, using the only vocabulary we have, the vocabulary of this world, transfigured by revelation.

That’s also why I don’t get bent out of shape when East and West describe the end with different emphases, purgatory and toll houses, different ways of mapping the same terrifying mercy of God onto human speech. Or when saints’ visions seem to tell slightly different stories. I’m not quick to assume contradiction, because I already expect translation.

In my humble opinion, neither the Greek nor the Latin, neither East nor West, fully captures the inexhaustible mystery in isolation. And I don’t think that means they have it wrong either. It’s more like I’m staring at one sliver of a diamond, and you’re staring at another. The light refracts differently from each cut. It isn’t opposing light, it’s the same light from the same source, reflected through different facets, each with its own shimmer. So yes, I can say both traditions hold the fullness of truth, not because every formulation is identical, but because the reality being confessed is bigger than any single register of human speech. Language is always a kind of reaching. It can be true, but it can’t be exhaustive. Even our most careful theological words are symbolic and analogical, not in the cheap sense of “mere metaphor,” but in the older sense, where symbols actually point to and participate in what they signify. We can speak truly, but we can’t speak God-sized. We can name what is revealed without pretending we’ve contained it.

It’s like the human mind is trying to remember the sound of the angelic choirs and then, back down here, trying to play it on a merely mortal instrument. The melody is real. The notes we hit are real. But we’re still tuning, still approximating, still saying something true with words that were never built to carry the full weight of glory.

And if that’s true, then the right response isn’t to argue louder, it’s to pray deeper. Let dogma keep us from lying about God, let symbol keep us from shrinking Him, and let the limits of language teach us humility. The point isn’t to solve the Mystery. The point is to be converted by IT.